W.W. Abell, Architect and Civil Engineer

By David Siegenthaler written for The Crackerbarrel

William Wright Abell, who lived in Elgin from 1873 to 1916, was one of Elgin’s most talented and respected architects. He was recruited to Elgin as a 19-year-old to work as a draftsman at the Elgin National Watch Co. by his uncle, Superintendent George Hunter. The historical Society Museum has two Abell technical drawings for watchmaking machinery, both dated 1879.

William Wright Abell, who lived in Elgin from 1873 to 1916, was one of Elgin’s most talented and respected architects. He was recruited to Elgin as a 19-year-old to work as a draftsman at the Elgin National Watch Co. by his uncle, Superintendent George Hunter. The historical Society Museum has two Abell technical drawings for watchmaking machinery, both dated 1879.

It is assumed that Abell helped design some of the watch factory buildings during their almost constant expansion during his time there. Here is a picture of the watch factory from 1874.

The first outside architectural design work by Abell that we know of were two buildings completed in 1885: the Oriental Roller Rink and the Teeple Barn.

The first outside architectural design work by Abell that we know of were two buildings completed in 1885: the Oriental Roller Rink and the Teeple Barn.

The Oriental Roller Rink, built during the height of a roller skating craze, was a huge 1- and 2-story building on South Grove Ave. just north of the watch factory. We have no photos of it, but it was described as “palatial” and “elegant” in newspaper reports. It had 11,000 square feet of hard maple skating surface and could seat up to 600. It also served as a venue for other large gatherings and burned down in 1895.

The Teeple Barn was a 16-sided barn built by Lester Teeple, a lumberman, who ventured into dairy farming. Realizing that his lumber was not long enough to build a standard 8-sided barn, Teeple asked Abell to design one with 16 sides. Located at the southeast corner of Randall Road and the Northwest Tollway, the barn was a stunning architectural and visual achievement. It was the only barn and one of only 47 landmarks and artifacts in the entire country to be included in the book, Saving America’s Treasures, published by National Geographic in 2001. This book beautifully describes the barn: “Latticed with cross braces and rafters and centered on an ingenious multipulleyed device for lifting and distributing hay, the shadowy interior achieves a level of Piranesian grandeur that makes “Teeple Barn” seem too modest a moniker; “Teeple Temple” is more like it. Architect W.W. Abell must have been conscious that he had created something truly noteworthy here: The cupola with which he topped off the building towers over the surrounding Kane County farmland like a big exclamation point.”

The Teeple Barn, the last 16-sided barn in Illinois, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. After the Teeple farm was sold in the late 1980s, preservationists spent years raising and spending money to keep it standing, efforts that were ongoing when a severe windstorm destroyed the barn in May 2007.

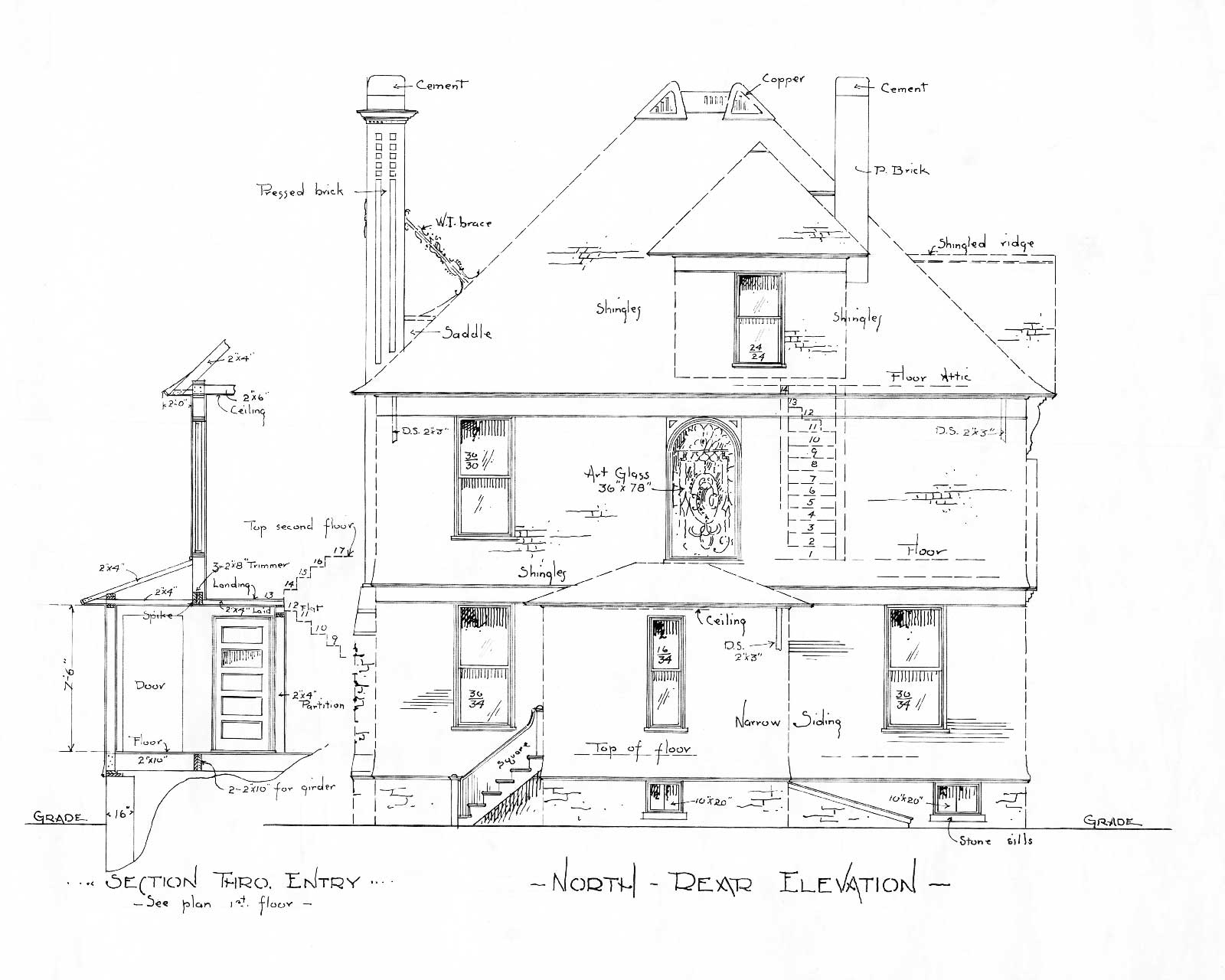

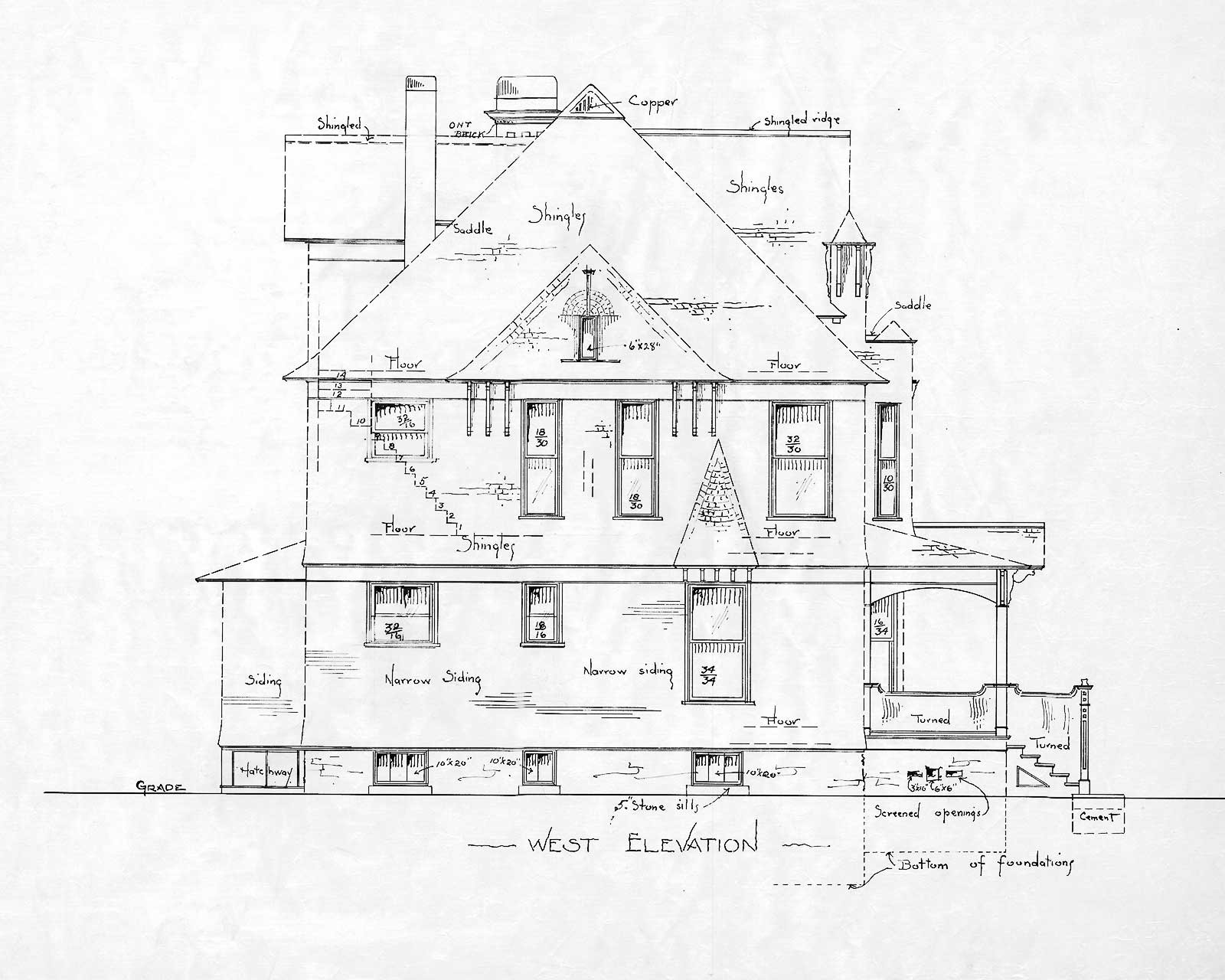

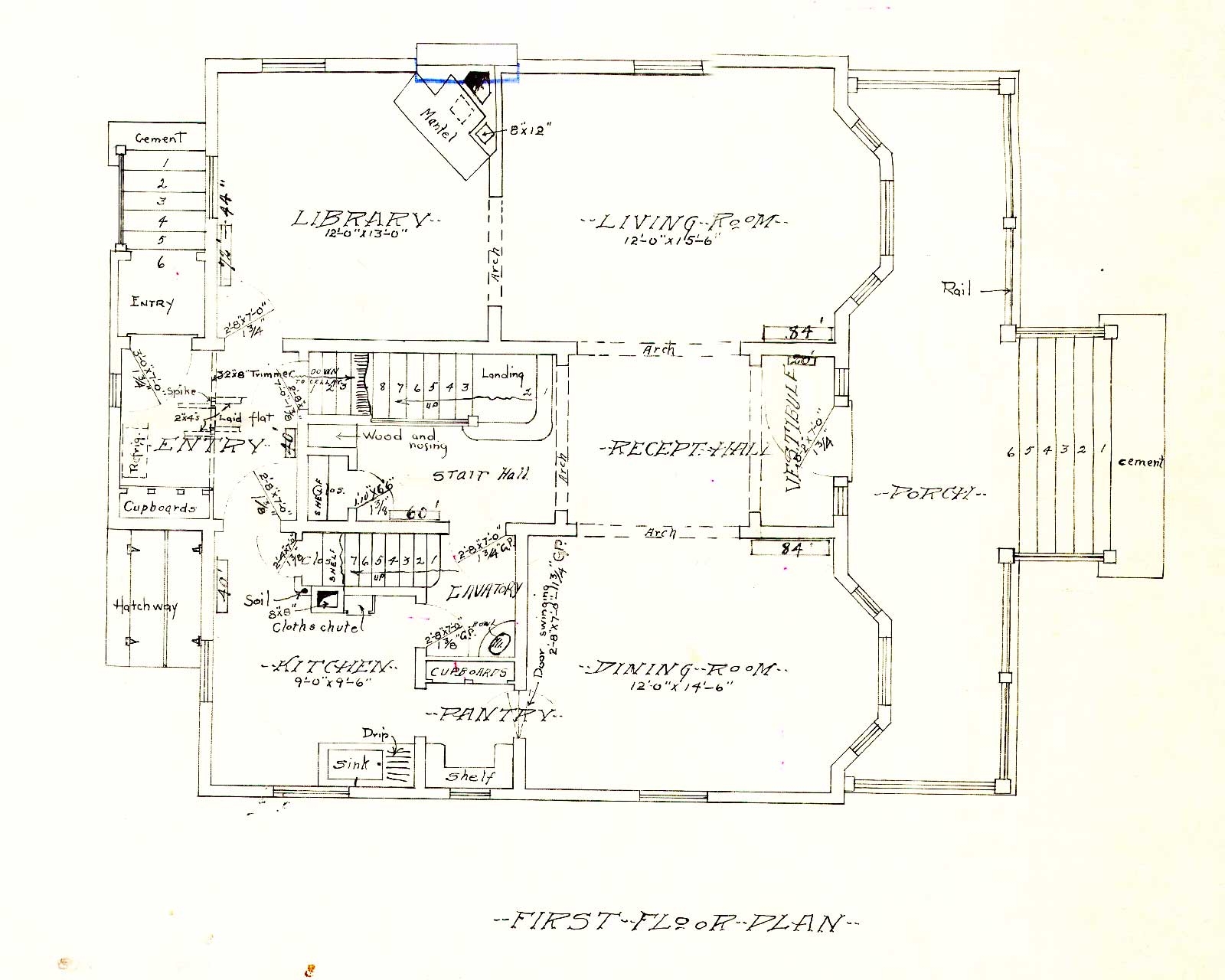

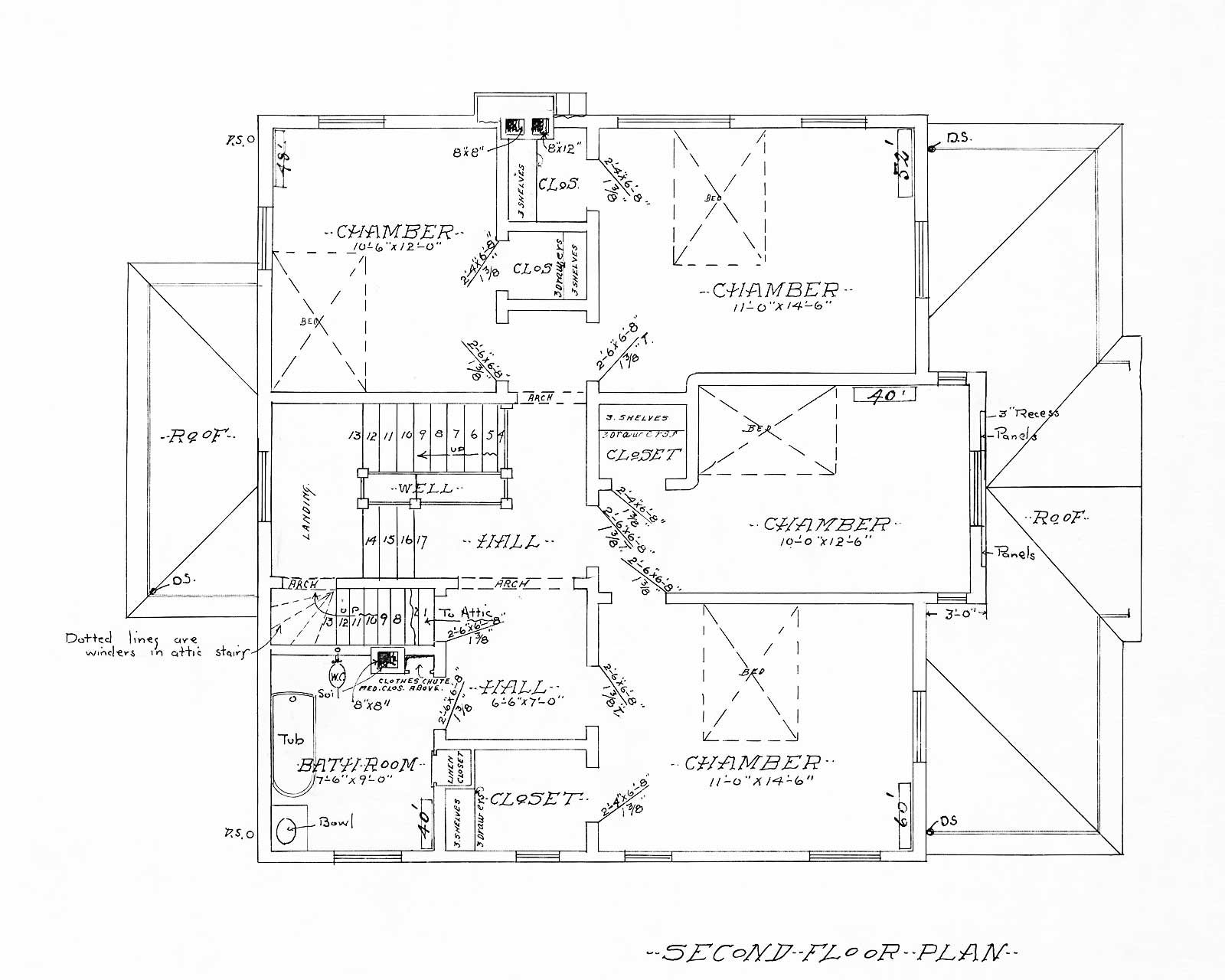

The first home designed by Abell that we know of was his own home, an attractive Queen Anne-style home at 527 Laurel St., built in 1888 shown. Abell worked at the Elgin National Watch Co. for nearly 18 years, until February 1891, when he entered private practice as an architect and engineer. He originally had offices in both Elgin and Chicago, but discontinued his Chicago office in 1894.

The first home designed by Abell that we know of was his own home, an attractive Queen Anne-style home at 527 Laurel St., built in 1888 shown. Abell worked at the Elgin National Watch Co. for nearly 18 years, until February 1891, when he entered private practice as an architect and engineer. He originally had offices in both Elgin and Chicago, but discontinued his Chicago office in 1894.

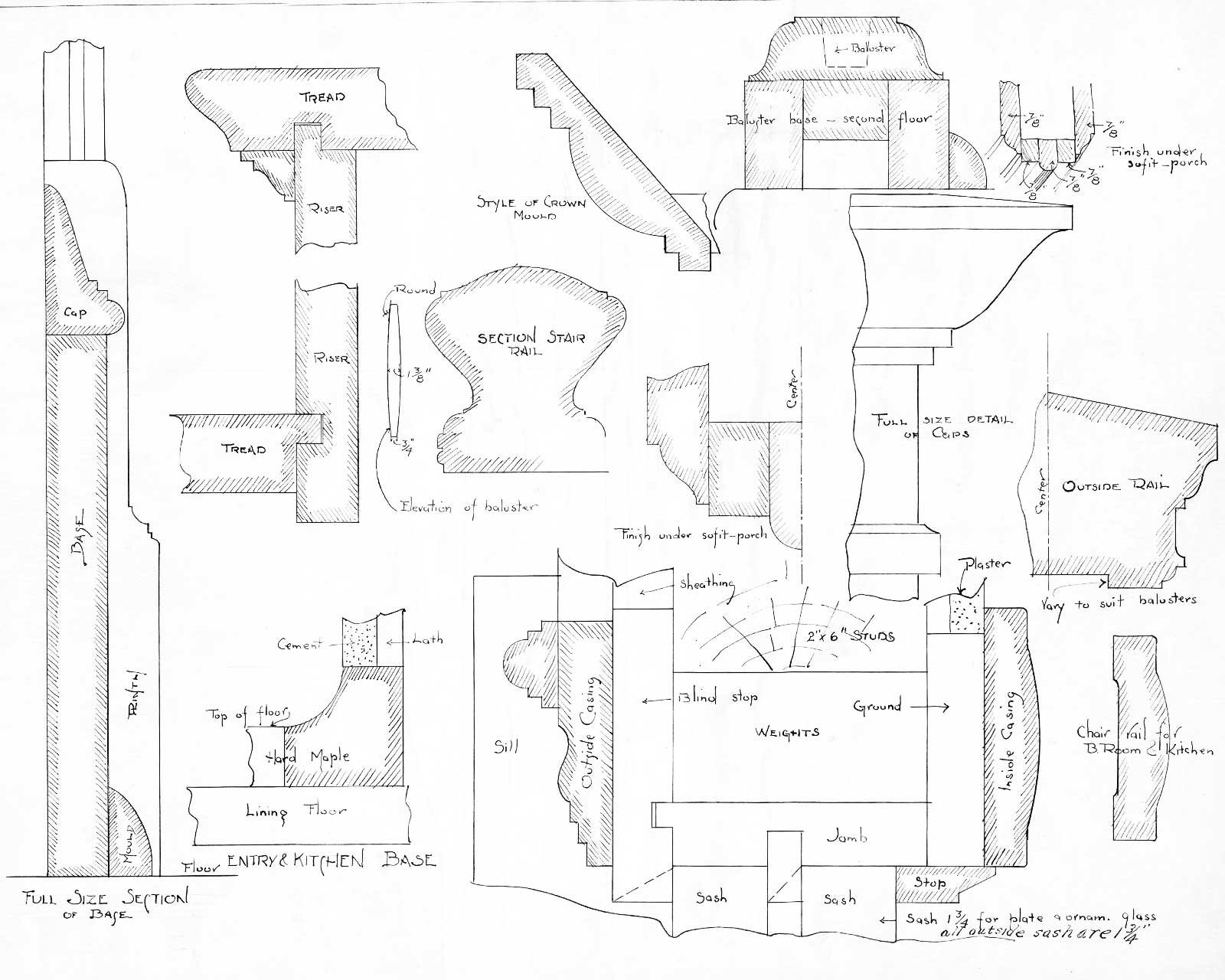

Though we know Abell primarily as an architect, his pre-watch factory training was mainly as a civil engineer. He worked for three different engineering firms in Massachusetts and Canada, including two that were involved in railroad building. Abell never gave up his engineering work. In 1888 he was appointed city surveyor. An 1893 newspaper building report noted that “aside from his architectural work, Mr. Abell has done more engineering than in any previous year.” His engineering skills were put to use in many of his buildings, allowing him to design ingenious solutions to complex problems. Examples are the multipulleyed device and trussing in the Teeple Barn; the erection of the Spurling Building (40 DuPage Court), which incorporated 180 tons of steel, atop underground springs; and the revolving automobile turntable in the basement of the George Cook home (70 S. Chapel St.). The basement entrance for an automobile is shown on the left below. The porches on the home are currently being restored using an old picture.

In 1891, his first year in private practice, Abell designed three big factory buildings: the Ludlow Shoe Factory shown below(630 Congdon Ave.; converted to residential units in the late 1990s);the Cutter & Crossette Shirt Factory (915 N. Liberty St.; razed 1964); and the Dickie Label Works (Wright Ave.; burned down 1904).

Also in 1891 Abell designed two churches which still stand: the First Presbyterian Church (240 Standish St.) and the Universalist Church (southeast corner of Villa Court and DuPage St.).

The Universalist Church may be the most unique and visible of the Abell-designed structures in Elgin. Co-designed by Superintendent George Hunter of the watch factory, this Romanesque Revival-style church was built in the shape of a pocket watch enclosed in a hunting case, as seen from above. The Universalists were a New England sect that reflected the values of the watch factory officials, who were overwhelmingly natives of New England. As noted in the book Elgin Time, the church’s design “was an architectural synthesis of the religious and secular callings of the membership.” The structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and today is owned by a Hispanic congregation, Iglesia Principe De Paz.

In 1892-93 Abell designed, in addition to many Queen Anne-style homes, three noteworthy buildings that still stand: the former Gail Borden Public Library (50 N. Spring St.);

the former German Methodist Church (76 S. Jackson St.); and the Spurling Building (40 DuPage Court). The 5-story Spurling, Elgin’s first steel-framed building, was the city’s tallest at the time. However, its impressive series of bay windows were removed in 1957 when the building was remodeled and renamed the Elgin Commerce Building.

In addition to the Universalist, Presbyterian and German Methodist churches, Abell also designed a fourth Elgin church that still stands: the former St. Paul’s Evangelical Church (1905-06; 224 Division St.). Some other notable Abell-designed buildings have been substantially altered over the years, such as the former Ackemann’s Department Store (1894-95; 168-70 E. Highland Ave.) and the former Old People’s Home (1905-06; 204 S. State St.).

Abell’s architectural work was not limited to Elgin. He designed homes, churches, schools and factory buildings throughout northern Illinois and beyond. According to his obituary, “during the years of his practice as an engineer and architect, he has built some work in almost every state of the union.” In Arlington Heights, the Prairie-style Banta House, added to the National Register in 1998, was designed by Abell and his son Ralph in 1908. He also designed, in 1906, the brick Prairie-style building with a shingled bell tower that served as Algonquin’s village hall until 1997. This landmark building still stands as a community center and looks exactly the same on the outside as Abell designed it. Algonquin’s St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, a Gothic Revival structure built in 1915 and razed in 1999, was one of Abell’s final designs.

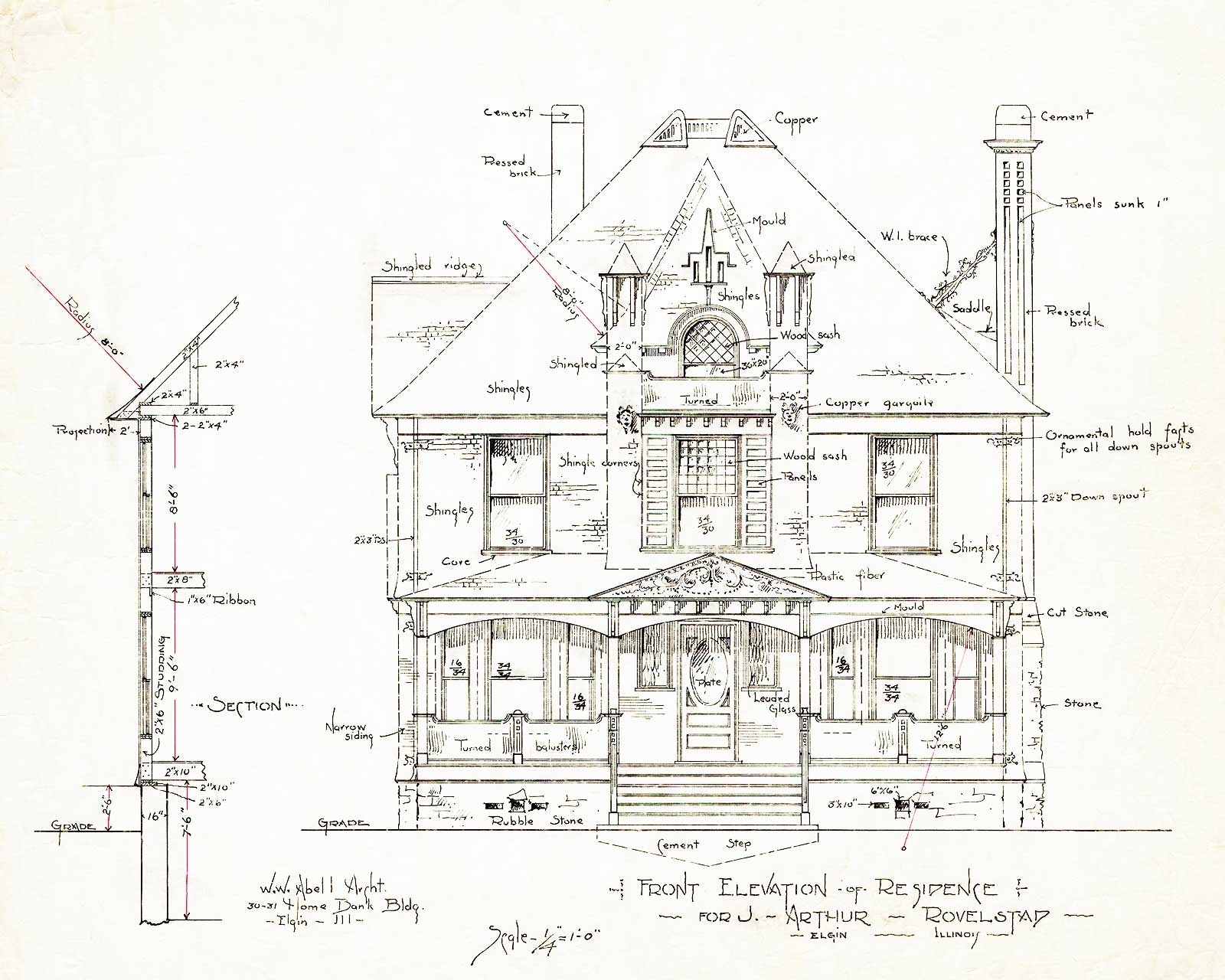

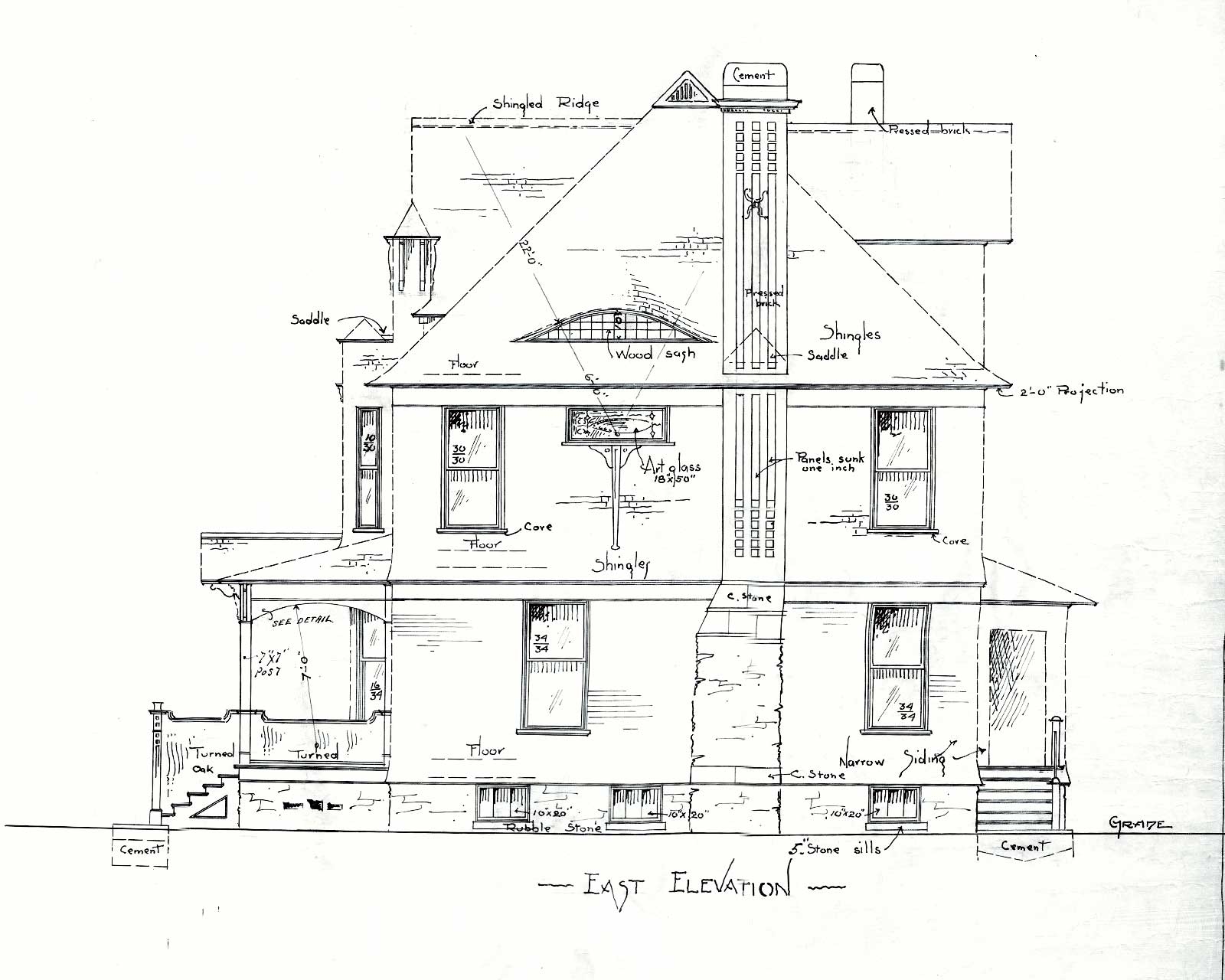

It is not known how many Elgin homes were designed by Abell, as documentation is lacking, but a rough estimate would be close to 100. He adapted as fashions in home design changed during his career, from the asymmetrical visual feasts of the Victorian era in the 1890s, to the more symmetrical Foursquares and Prairie-style homes of the early 1900s. There are Abell-designed homes all over Elgin but the highest concentration may be in the 700- and 800-blocks of West Highland Ave., where there are seven.

Here are two examples of Abell’s attractive Queen Anne-style homes: the Finla McClure mansion (1891; 770 W. Highland Ave. and the David Sharples home (1892; 303 River Bluff Rd.).

William Wright Abell was born in Cummington, Massachusetts on November 7, 1853, the first of three children of Joshua L. and Mahala Connor Abell. William’s siblings were Rodolphus Elliott (1858-1942) and Ashley J. (c1863-1922).

In 1873, at age 19, William came to Elgin to work as a draftsman at the Elgin National Watch Co., where his uncle, George Hunter, was the superintendent. Hunter had married Louise Connor, a sister of William’s mother, in 1858 and six years later became one of the “Seven Stars” recruited from the Waltham watch factory to start-up the Elgin watch factory. William worked at the watch factory for nearly 18 years, designing both watchmaking machinery and factory buildings.

As a young man William was an avid French horn player. During his watch factory years he managed the Cornet Band, the Bluff City Band and, finally, the Elgin National Watch Factory Military Band, which was a consolidation of the other two. The band traveled extensively, especially in the Midwest, and helped to advertise Elgin watches.

William passed away at age 62 on January 23, 1916 from valvular heart disease and was buried in Bluff City Cemetery. He would be proud to know that 100 years later most of his works still stand as a testament to his brilliance, and that appreciation for his talent has never waned.

Acknowledgements: Mike Alft’s books and newspaper articles; Elgin Time: A History of the Elgin National Watch Company, 1864-1968 (by Mike Alft and Bill Briska, 2003); Saving America’s Treasures (National Geographic, 2001); newspaper building reports; obituaries; federal censuses; city directories; etc.